Mona and Sanaa Seif never wanted to be political activists. On the contrary, as children, the sisters rebelled against their political parents. When their father, a human rights lawyer, and their mother, a university professor, spoke non-stop at home about the criminal, corrupt and repressive Mubarak regime, the children would turn off. They were barely teenagers before boredom made them rebel against their parents’ mission and they refused to have anything to do with the opposition movement. That was until they realised that politics had cruelly caught up with them a long time ago.

Was she the daughter of a criminal? At some point, it all became clear: The fate of her family lay in someone else’s hands.

The violence of the new regime under President Abdelfatah al-Sisi soon became a permanent backdrop to their lives, says Mona Seif. The 35-year old cancer researcher from Cairo is well-known. Ever since the 2011 revolution, she and her family have been in the spotlight of Egypt’s activist scene. The roar of the repression steadily increased over the last ten years. The story of the Seif family casts a sombre shadow over the post-revolutionary decade in the country. It’s a story of despotism, of the resilience of a strong woman and her family, and the story of an uncertain future – which could either find its resolution in freedom or in permanent repression.

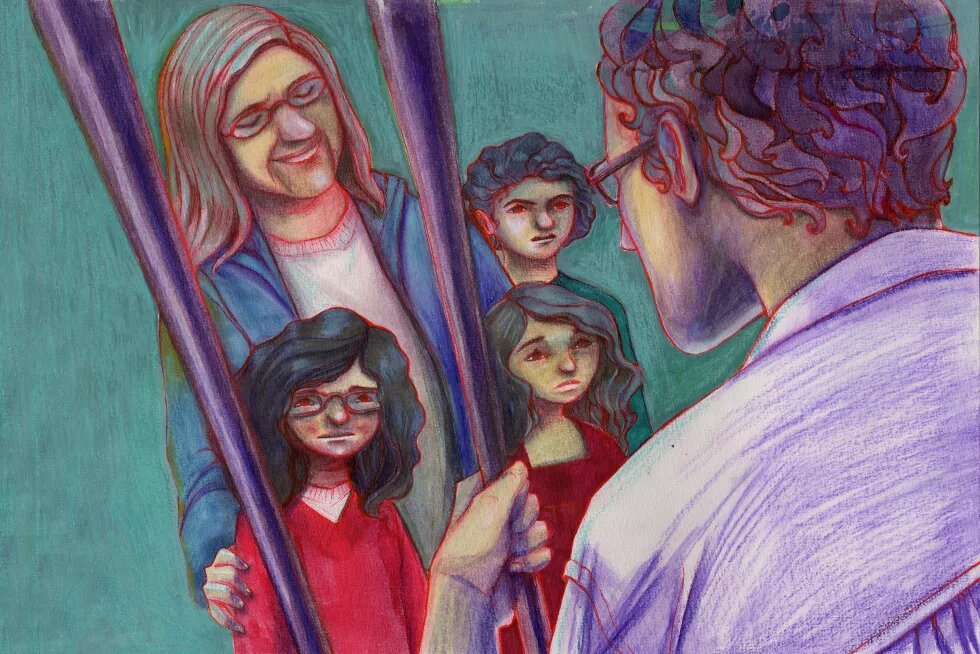

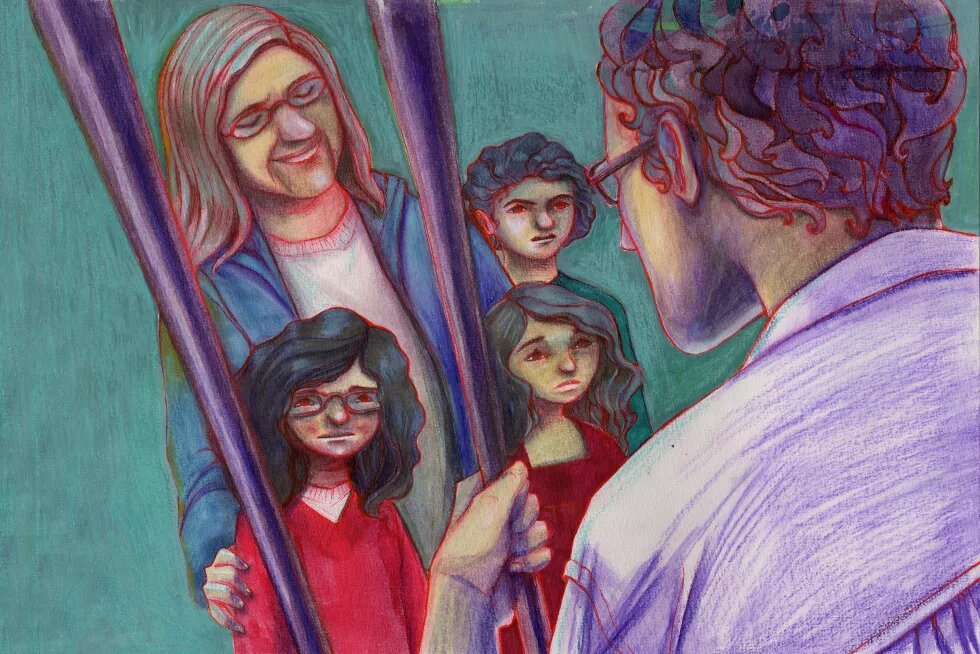

Of course, it didn’t all start in 2011. »When I was young, I was often in prison,« says Mona Seif. Her father was a political dissident and spent what felt like an eternity behind bars.

It was certainly a large part of her childhood. At times he was at home, at times in prison where his children were able to visit him regularly. Mona Seif remembers those visits well.

As a child, she used to ask herself one thing: Why? Back then she simply couldn’t understand why her father was in prison. Was she the daughter of a criminal? At some point, it all became clear: The fate of her family lay in someone else’s hands. She went to her first demonstration in 2007 organised by a union in solidarity with imprisoned lawyers in the country. Many of her friends were arrested that day. A short time later her brother, Alaa Abdelfatah, a well-known software developer and blogger, was captured by the regime. It was then that Mona Seif realised she had to become a dissident herself.

What ultimately politicised her, says Mona Seif on the phone, was the death of the blogger Khaled Said. On June 6th, 2010, Said was beaten to death in the middle of the street in Alexandria by police.

His death sparked a wave of protests across the country. From all corners of society, people came together, on the internet and in local protest groups, and went out onto the streets, calling for justice.

Said’s death brought to light the reality of police brutality in Egypt. »Khaled Said’s fate had direct links to my own life, to my existence, to my family history. I saw myself in his story and didn’t want something like that to happen again. And certainly not to anyone in my family,« says Mona Seif. »Stop killing us!« Mona Seif chanted on the streets and she still keeps on having to repeat it today. But is that maybe asking too much of Egypt?

After 2010, millions of people were at once drawn together by a turbulent mix of emotions: Solidarity, empathy, anger, grief, courage, weakness, anger, desperation, and hope. Ten years later and the situation in the country hasn’t calmed down. In the face of this ongoing emotional turmoil, Mona Seif has just one wish: »I want and need a break. That’s all.«

Prison became a regular feature of her family life in 2010. The three sisters themselves often ended up in police stations, in courtrooms, and ultimately in prison cells. For nearly ten years now Mona Seif has been fighting tirelessly for the freedom of her loved ones. »By now we’re just exhausted. We’re tired and really don’t have any more energy,« says Mona Seif. Still, no end is in sight in this exhausting game between unequal opponents. »I can’t go on anymore,« says Seif.

It’s exhausting, but I can’t let them erase my humanity.

Sometimes she just can’t understand why her family is so hated by the regime. It’s partly due to personal enmity from individual members of the secret services, the police, or the state prosecution – and partly because of the anarchy within the authoritarian regime. In the case of the Seif family, a judge has made it his goal to crush Alaa Abdelfatah, Sanaa, and Mona in the iron grip of the regime. Any person who does not pay homage to the dictatorship is up against the wall - and those in power stand above the law. »Thousands of Egyptians who haven’t done a thing are sitting in prison. Just because,« says Mona Seif, perplexed. »And if, when faced with this repression, people don’t immediately give up and stop behaving like rational human beings the regime wonders: How come these people are still standing before us? How come they can still speak and have a will of their own? Egypt’s rulers want to stamp the dignity out of their opponents. It’s exhausting, but I can’t let them erase my humanity.«

A lot happened in Egypt in the years after the 2011 revolution: The toppling of the long-time dictator Hosni Mubarak, democratic elections, the rise and fall of the Muslim Brotherhood, a military coup, a string of financial crises, numerous terror attacks, a little-known war on the Sinai peninsula, feminist protests against sexual violence, a crackdown on the press and freedom of speech, the continuing authoritarian backlash from the regime – and thousands of politically motivated murders. »My head is spinning,« Mona Seif wrote recently on Twitter where she has nearly 600.000 followers. Reading Mona Seif’s tweets makes it clear that the country is still engulfed in crisis. One scandal is barely over before the young activist is having to comment on the next: When dissidents and demonstrators are crushed by tanks, when people are arbitrarily shot at during protests, when members of the opposition are kidnapped by the security services and tortured to death, when political prisoners disappear and are forgotten.

Mona Seif is always posting about her brother and sister on Twitter because she cannot and will not forget them. The likes and encouragements from her followers appear helpless and depressing. Even when there’s a bit of good news the respite doesn’t last long: In March 2019, her brother, Alaa Abdelfatah, was briefly released from prison after five years. He was accused of organising protests without permission. His family says the charges were pulled out of thin air. Yet, after his release, he still had to report to the police every evening for another five years. »Surveillance« is the term in the Egyptian justice system for this type of punishment. In turn, Alaa Abdelfatah swore to stop writing blogs, to stop going to demonstrations, to concentrate on his family and his work. He withdrew completely from the activist scene.

»He simply didn’t want to go back to prison again. But in September 2019 they just arrested Alaa anyway,« says Mona Seif. That time the regime accused him of terrorism. It’s essentially irrelevant whether they have actually done anything to offend the elite. »If they want to, they just come and detain us.

it’s just not an option for her to back down: Give up and you die.

They simply hate us and when they do this it sends out a clear signal to all the others.« Throttle the protest before it gets a chance to take root: That seems to be the strategy adopted by the Egyptian security services. Still, Mona Seif isn’t afraid anymore and she speaks her mind: Life has only got worse since President Abdelfatah al-Sisi came to power. And repression is just stupid because it leaves the opposition with just one option: To carry on to survive.

And so the Seif family was drawn back into the thick of it; into having to fight for their freedom. Laila Soueif, Mona Seif’s mother, is a maths professor at Cairo’s university. The feminist and human rights defender is well-known in Egypt for her fearlessness. Her daughter, Mona Seif, draws strength from watching her mother: »She’s been doing this much longer than me and she’s just as strong and determined as ever.« The regime knows that Soueif is well-connected in the academic world. The majority of students stand in solidarity with the Seif family and their fight for freedom. As such, their situation could spark another wider political movement, as did the death of Khaled Said in 2011. »Maybe that’s why the regime has us in its crossfire and doesn’t shy away from using the most brutal methods against us,« says Mona Seif. Still, it’s just not an option for her to back down: »Give up and you die.«

At the end of June 2020, Mona and Sanaa Seif and their parents camped outside Torra prison in the south of the capital city, Cairo. They were demanding to be allowed to speak to their brother and to find out about his physical and mental health. The regime had restricted visits and stopped all communication with his lawyers. Held in isolation, Alaa Abdelfatah started a hunger strike. His family continued to repeat their demands for access to information and a fair trial. They slept on the pavement in front of the high-security prison in order to draw attention to Alaa Abdelfatah’s situation. That was until a group of female thugs came and attacked them. The regime often pays gangs to go round and crush political activism.

We were demonstrating peacefully for our rights, we were even sat silently. They brutally beat us up. That’s my reality, that’s our reality.

Breathless and running from the scene of the assault, Mona Seif records a video on her phone. She describes being dragged across the pavement by her hair, which still stands on end. »They hit us, they tried to grab my bag off me. They beat us up. The police just watched whilst all this went on and did nothing,« Mona Seif explains. The video will later go viral as tens of thousands watch it on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. A group of women, dressed in black, wildly assaulted the family, according to reports from the press and human rights organisations. It was her little sister, Sanaa, who bore the brunt of the attack, says Mona Seif. »We were demonstrating peacefully for our rights, we were even sat silently. They brutally beat us up. That’s my reality, that’s our reality.«

Not much later the 28-year old Sanaa Seif, Mona’s little sister, and a well-known filmmaker was arrested on spurious charges. She stands accused of spreading fake news. Yet again, the Egyptian justice system has shown how quick they are to adapt and adopt terms from the West for their own motives. Sanaa Seif is still in prison. An international campaign has gathered to call for her release, including Hollywood stars like Danny Glover, Maggie Gyllenhaal, and Thandie Newton, as well as famous authors such as Noam Chomsky, Arundhati Roy, and J. M. Coetzee.

»What’s wonderful is that these protests and other ones sprung up spontaneously. We, the family didn’t have anything to do with them,« says Mona Seif. This doesn’t mean she gets to have that long-awaited break, but international solidarity does lighten the burden.

Mona Seif says too that her family is privileged, well-connected, educated, financially stable, and internationally known. That makes it easier for them to deal with their fate, unlike other activists or Egyptians who are politically active.

Still, she’s running on empty. »The regime has forced us into full-time activism,« says Mona Seif. Their lives have become an unrelenting cycle of courtrooms, protests, meetings with lawyers and the press, and prison visits, followed by sleepless nights. A return to normal life after the intensity of this past decade is unthinkable. No one survives unscathed from ten years of this sort of stress. »But,« she says, »it is some sort of solace to know that we are many.«