Mother of the revolution

Ola al-Jundi has a broad smile on her face when she has her children around her. The 48-year old secondary school teacher runs a primary school for Syrian refugees in the Bekaa valley, in Lebanon. Her classroom is a simple construction made of boards and tarpaulin. Inside, it’s hung with pictures drawn by her pupils. In one of her videos, Ola al-Jundi stands smiling in front of a group of young girls, their hair in neat plaits, and ponytails. The children are in a circle, clapping their hands, nudging one another whilst skipping back and forth. They’re playing a game that adults will probably never fully get the hang of. Still, Ola al-Jundi does what she always does; she looks on with enthusiasm.

Despite all this, al-Jundi is deeply unhappy. She can’t hold back her tears when she talks about her memories of the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011. For her, it all began in the village where she was born and spent a significant part of her life. It’s called Salamiya and is a short distance from Hama. The name of her village derives from the Arabic word Salam, which means peace.

Why couldn’t Syrians gain their freedom peacefully? Ola al-Jundi has been asking herself this same question again and again for nearly ten years. It’s fair to say that her search for an answer may well pursue her for the rest of her life.

From the start, our revolution was bigger than just another sectarian war.

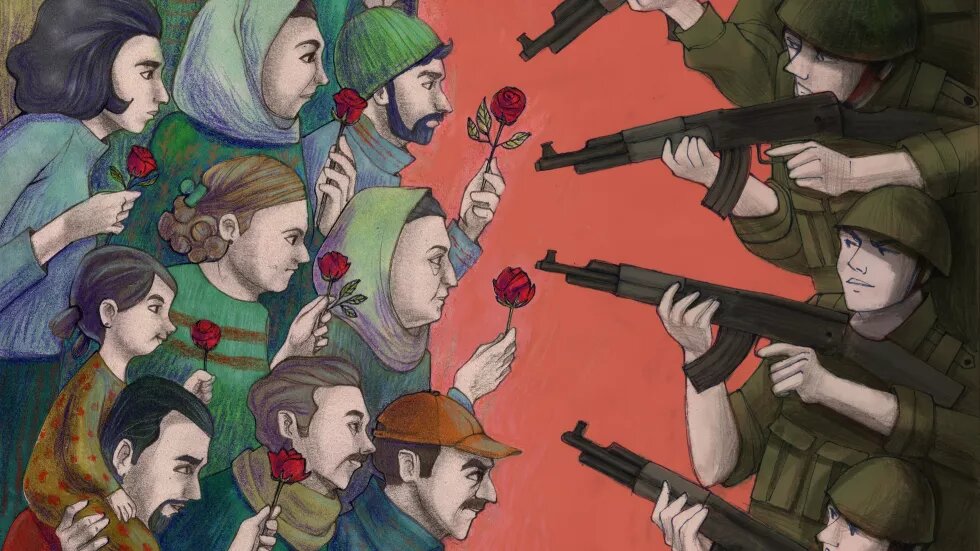

Ola al-Jundi’s father was also a teacher and a member of Syria’s opposition Communist Party. The community in Salamiya always came together to help one another out. As one of eight children, Ola al-Jundi decided early on that she wanted to give something back to her community. The moment came on March 28th, 2011 in her village. The first demonstration against the Assad regime was about to take place around Hama. »Back then it was a true revolution. The regime tried to depict the protests as Sunni against Shia,« Ola al-Jundi remembers. Like most of the people living in the region, her family belonged to the Ismaili community, a subset of Shia Islam. According to the regime’s ideology, someone like Ola al-Jundi could not protest against Bashar al-Assad and his clan, who themselves were members of the Shiite Alawi minority. »From the start, our revolution was bigger than just another sectarian war,« says al-Jundi.

»I took my two small children with me to the protest,« she carries on, laughing. A daring decision it would seem now. At the time, however, she couldn’t anticipate how far the regime would go to secure its power. Back then it felt natural to take the children with her. Ola al-Jundi never kept her opposition to the Assad clan a secret. Alongside the other intellectuals in the village – the teachers, doctors, and journalists – she explained to the people why it was important now to stand up for their rights. Ola al-Jundi estimates that they won over roughly a quarter of the villagers immediately.

»I was in charge of the Facebook posts and was responsible for coming up with the chants. I was always marching up at the front next to the banners and got everyone chanting,« says Ola al-Jundi. »The Syrian people are one,« she shouts rhythmically into the telephone.

It sounds even more striking in Arabic and for Syrians, it was particularly important to call for unity in their deeply heterogeneous society. »What was most important to us, however, were the women,« says al-Jundi. They were supposed to prove that these were peaceful demonstrations. Yet this didn’t have much of an impact on the regime.

Together they organised childcare, making sure that one mother from each large family or neighbourhood always stayed at home with all the children. »That way, in case we died or went to prison, someone was always with our children. You see, gradually our husbands had all ended up in the torture chambers of the secret service.« Soon the crackdown came to Salamiya as well. The regime used all its means to get women off the streets. Because without the women it was easier to convince the outside world that instead of peaceful demonstrators these were terrorists. It wasn’t just the rhetoric. These were carefully laid plans for a war that would eradicate hundreds of thousands of lives with barrel bombs, hails of rockets, orchestrated starvation and expulsions.

And it was a great feeling! For the first time, I thought, I’m a person. The more often I shouted that the Assads should disappear the more I felt like a human being. It was so liberating.

When Ola al-Jundi was released again from prison at the end of 2012 she realised something had changed: Suddenly lots more actors were involved in the events in Syria. »I noticed that a lot of Russian media reports were appearing in my Facebook feed. They all claimed that our revolution was illegitimate and should be ended.« Still, Ola al-Jundi felt compelled to go back onto the streets. »And it was a great feeling! For the first time, I thought, I’m a person. The more often I shouted that the Assads should disappear the more I felt like a human being. It was so liberating.«

Yet, a lot fewer women did turn out for the protests. Day by day the situation became more complex, descending further into chaos. Sometimes the police arbitrarily picked up men from the roadside and threw them into the back of their vans. The vehicles drove off and the men disappeared. At other times, gangs linked to the regime indiscriminately attacked people in their homes. Fires broke out, snipers hid out on the rooftops and fighter jets flew over their heads.

Still, Ola al-Jundi didn’t give up believing in the utopia of a free and peaceful Syria. »Some of my pupils told me I should get myself and my family to a safer place.« Her pupils, friends, and family thought she was taking too many risks considering the all-powerful nature of the dictatorship. After receiving a tip-off that the regime intended to kidnap her she finally fled with her family to Lebanon.

I wanted to pass on a better country to my children. I saw the revolution in 2011 as a part of my duty of care.

»It’s so painful but I still enjoy thinking back to the first days, weeks and months of our revolution,« says al-Jundi today. Her memories are mired with sadness because she knows she may well never experience those good feelings again. The utopia of the early days remains a utopia in their minds. »I wanted to pass on a better country to my children. I saw the revolution in 2011 as a part of my duty of care,« says a resigned al-Jundi. For her, the revolution was a part of being a mother. »Syrian mothers and their superpowers should never be underestimated,« she adds, laughing.

Now she lives a long way from her son who made it to Sweden with his father. And from her daughter who is studying in Canada. The distance weighs heavily on her. A letter from Sweden reached Ola al-Jundi in Lebanon in 2018, stating that she could go and live with her family in Sweden, should she wish. The Swedish authorities had authorised the family reunification process. By 2018, however, it was too late. Al-Jundi had already taken charge of hundreds of children in her refugee camp after pulling together 2000 dollars to build the school four years earlier.

»I couldn’t abandon them and go to Europe,« she says, thinking about Sweden. She’s also still too attached to Syria. Sweden would be far too far away. She would no doubt lose her utopia completely there. In Lebanon, not far from her home country, she could still somehow imagine that everything could turn out for the best. Mid conversation the connection breaks down. The electricity has cut out, as it so often does in the Bekaa valley. It takes a few minutes for the internet to get back up and running. When al-Jundi calls again she says she does sometimes question what she did and wonder if the revolution was the right thing. Then she thinks again that she and all the other Syrians who were demonstrating peacefully against the regime in Salamiya and across the country simply had no other choice.